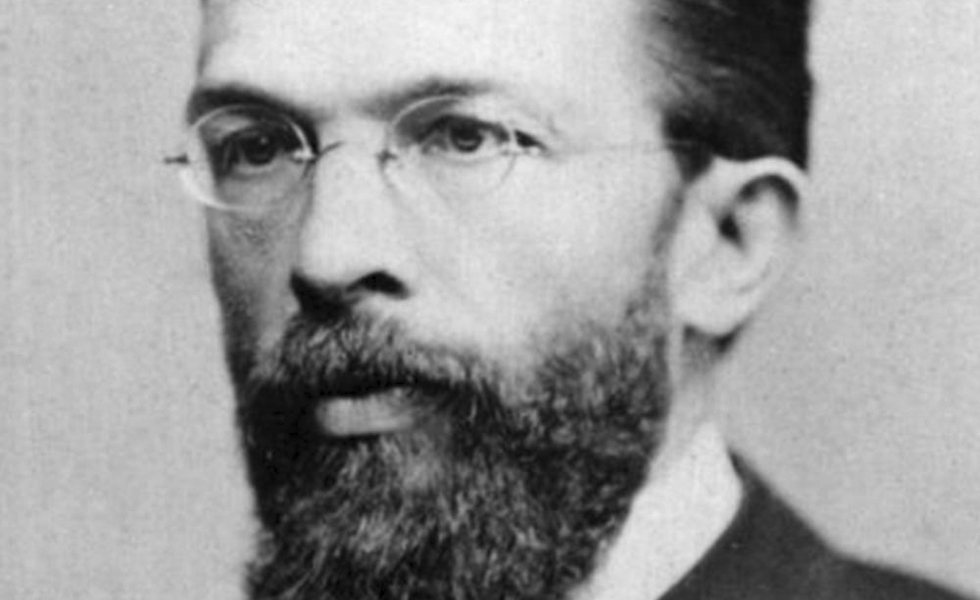

Carl Menger, Founder of the Austrian School of Economics

Texte d’opinion publié en exclusivité sur notre site.

Carl Menger was not only the founder of the Austrian School of Economics; he also became one of the pioneers of modern economics with the 1871 publication of his classic work, Principles of Economics. Like his disciples after him, Carl Menger, born in 1840 in the Austrian Empire, was both a man of thought and a man of action. He began his career as a journalist, and was subsequently a ministry staffer, an academic, a tutor to the imperial crown prince, and an economic advisor to the Austrian government. Among his numerous contributions to economic thought, three stand out.

The first marked the history of economics thanks to a notable coincidence: In the early 1870s, three intellectuals who didn’t know each other, living in three different European countries, made a simultaneous discovery concerning the notion of value. Along with Menger, Léon Walras of Switzerland and William Stanley Jevons of England realized that the value of a good does not depend on the quantity of work devoted to its production, as classical economists from Smith to Marx had maintained, but on the utility consumers place on obtaining one additional unit of the good. It is this additional quantity “at the margin” that counts, which is why this discovery was described as the “marginal revolution.”

Among the three discoverers, Carl Menger is the one who placed the most emphasis on the subjective nature of the theory of value, which explains numerous economic phenomena that confront us every day. Starting from the logic of diminishing marginal utility (the more of a good I consume, the less utility I get from the next unit consumed), we can thus explain why water in a desert will be expensive, whereas next to an abundant source, it will be cheap. Scarcity, in other words, helps explain value.

To take a contemporary example, why can the price of an Uber trip suddenly become higher in the space of a few minutes when nothing has changed about the cost of producing the service? Simply because in certain contexts, for example when it rains, there are suddenly more consumers who are ready to pay extra for this mode of transportation because they place greater value on an additional trip. This pushes up the price, which attracts available drivers ready to profit from this demand. The market thus tends to provide more consumer satisfaction when prices are flexible and better reflect the value of goods.

Menger’s second original contribution is a methodological one. He disagreed with the German Historical School which taught that economics could only be understood through the study of historical facts. In contrast, the Austrian believed that it is possible to use logic to deduce general laws that can help us understand complex economic phenomena. Theory provides us with tools to help us better analyze facts and organize them in a coherent manner in order to deduce more general laws.

In order to understand society and economics, one has to start with individual actions by considering that everyone tries to maximize his or her interests and satisfy his or her needs. Menger therefore posited the foundations of methodological individualism, which is not the homo economicus caricature to which economics is too often reduced. According to Menger and the Austrian economists, individuals are not omniscient and do not know everything about the future. We often make mistakes, and are constantly revising our expectations.

Menger was also a philosopher who thought about the nature of the institutions that govern our daily lives. How do institutions like language, money, and morality arise? In contrast to his adversaries from the German Historical School, Menger thought that these owe nothing to governments or to centralized political power, but are explained instead by the spontaneous emergence of conventions progressively accepted within communities. For example, in the case of money, certain individuals discovered that barter was not practical for exchanging goods that do not share the same characteristics. They realized that certain goods that were more tradable than others could serve as intermediate goods in exchanges. This convention was progressively accepted and eventually used universally without the intervention of any centralized organization.

The Nobel laureate economist Friedrich Hayek pursued this line of thinking with his theory of spontaneous order: Institutions and rules of law arise through trial and error. They are the fruit of human action, but not of centralized human planning.

Carl Menger’s disciples in Vienna, Eugen Böhm-Bawerk and Friedrich Wieser, continued to formalize and develop his approach. Several more generations of Austrian economists have since been trained, the most famous being Hayek and Ludwig von Mises. The “Austrian” school today is blossoming around the world. Thanks to Menger, it proposes an original vision of economics and society, and it still has much to offer today.

Jasmin Guénette est vice-président aux opérations de l’Institut économique de Montréal. Il signe ce texte à titre personnel.