Wireless Services: Should Regulation Favour Resellers?

The Canadian government and the CRTC have adopted various policies over the past decade aimed at increasing the number of players in the wireless sector. Although such policies have had several negative consequences, there is today a well-established fourth wireless provider, owning its own infrastructure, in almost all regions of the country. Ottawa now wants to push this interventionist logic even further by favouring resellers (called Mobile Virtual Network Operators, or MVNOs, in telecom jargon). Would such a policy bring more competition to the telecommunications industry and the intended benefits to consumers?

Media release: Wireless services: The CRTC should not favour resellers

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Why favouring wireless resellers undermines competition (The Globe and Mail, December 4, 2017) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Martin Masse, Senior Writer and Editor at the MEI, and Paul Beaudry, Associate Researcher at the MEI. The MEI’s Regulation Series aims to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

The Canadian government and the CRTC have adopted various policies over the past decade aimed at increasing the number of players in the wireless sector. Although such policies have had several negative consequences,(1) there is today a well-established fourth wireless provider, owning its own infrastructure, in almost all regions of the country.

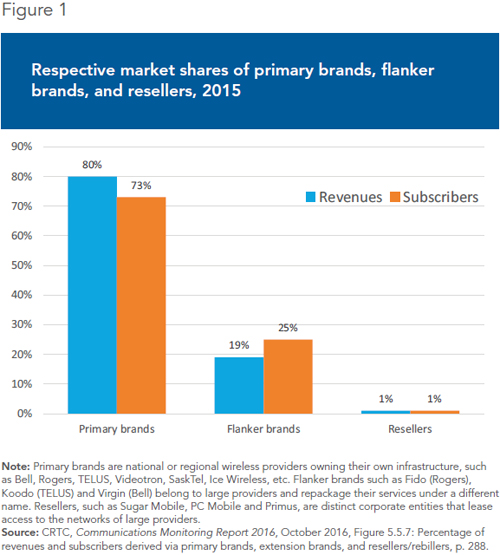

Ottawa now wants to push this interventionist logic even further by favouring resellers (called Mobile Virtual Network Operators, or MVNOs, in telecom jargon).(2) These are very small players that have no wireless network of their own, but instead lease access from larger players and resell a cheaper service. Resellers are distinct corporate entities, unlike so-called “flanker brands,” which belong to large wireless providers but market their services under a different brand for a different type of clientele (see Figure 1 showing their respective market shares).

Would such a policy bring more competition to the telecommunications industry and the intended benefits to consumers?

Redefining the Mandated Wholesale Roaming Regime

One of the rules of the current regulatory regime is that wireless providers are obliged to offer wholesale roaming on their networks to other wireless providers at regulated prices. This is to ensure that Canadians are able to use their devices anywhere in the country, including in areas where their provider has no cellular towers.

However, the CRTC has always refrained from forcing providers to share their networks with resellers, as is done in some countries, since this would contradict its stated goal of encouraging “facilities-based” competition, or competition between providers owning their own infrastructure. Facilites-based competition is rightly seen as the best way to spur more investment in the sector and more overall network capacity.

The main technical difference between the two situations is that clients of providers with infrastructure need to roam on other networks only incidentally, when they travel outside their provider’s “home network,”(3) while clients of resellers need permanent access to these networks, since resellers have no network of their own.

In June 2017, however, following a dispute between Rogers and a small reseller called Sugar Mobile,(4) the Innovation Minister asked the CRTC to reconsider this distinction and see if a broader definition of “home network” that would include Wi-Fi should instead be adopted.(5) This is because Sugar Mobile’s clients use their devices primarily by connecting to Wi-Fi networks (either through their own personal or workplace Internet connections, or free Wi-Fi hotspots in public venues such as restaurants, coffee shops, public transit, and libraries). They need to connect to the wireless network of a provider only when no Wi-Fi network is available.

If the CRTC were to adopt this broader definition, Sugar Mobile and other resellers would then be treated like any regional wireless provider with its own infrastructure, even though they possess no towers or spectrum licenses, and no Wi-Fi network. They would therefore benefit from the mandated wholesale roaming regime and be able to access the networks of facilities-based providers at regulated rates.

The Negative Impacts of Favouring Resellers

There are several reasons why the CRTC should stand its ground and refuse to adopt regulations that would artificially favour resellers.

Groundless justifications

Some of the minister’s justifications for the proposed change are groundless. For example, it is not true that “Canada has among the lowest adoption rates for mobile wireless telecommunications services among industrialized countries.”(6) This assertion is drawn from a misleading OECD comparison based on the number of SIM cards per inhabitant (as opposed to the proportion of wireless users in the overall population). In many countries, users have more than one card for the same device in order to save money, which results in absurdly inflated “penetration rates,” in many cases far above 100%.(7)

The fact is that the vast majority of Canadians (81.6%) had a wireless device in 2015, a proportion that keeps increasing.(8) Canadians are among the biggest users of data on tablets and smartphones (sixth out of 21 countries surveyed by Cisco for both categories). Moreover, in terms of smartphone market penetration, Canada ranks third out of 21 countries surveyed with a total of 83% of mobile subscribers using smartphones. And it ranks fourth in term of the proportion of mobile users connected to the fastest network.(9)

As Canada has one of the best wireless infrastructures in the world, and Canadians are among the most avid consumers of data in the world, there is no need to intervene in order to catch up with other countries.

Commercial agreements are already possible

It is already possible for resellers to conclude wholesale roaming agreements with wireless providers on a commercial basis, and there are a number of resellers in Canada such as PC Mobile and Primus. It may indeed be profitable for wireless carriers to strike agreements with resellers when they have surplus network capacity, instead of leaving it unused. In this case, the presence of resellers ensures a more optimal use of resources, while providing more choice for consumers in specific niche markets and those looking for a cheaper alternative.

If it is in the financial interest of parties to enter into commercial agreements, they will happen, and they will benefit both the industry and consumers. If they cannot be reached voluntarily, it is because there is no benefit to be had and they should not be mandated by government regulation.

Artificial competition

Proponents of forcing wireless providers to share their networks with resellers at regulated rates argue that it will foster more competition and bring lower prices and better services to consumers. But propping up small players without a profitable business model by giving them privileged access to the resources of other providers can only sustain artificial competition, without any of the benefits entailed by real competition in a free economy.

Such false competition is not based on sound rivalry. It doesn’t increase the amount of resources or capacity on offer. And it doesn’t foster innovation. On the contrary, it undermines the incentives of owners of infrastructure to invest and innovate, because they will have to share the resulting benefits. It also does not encourage resellers to invest in order to build their own infrastructure, since they piggyback on someone else’s at prices guaranteeing them a margin of profit.(10)

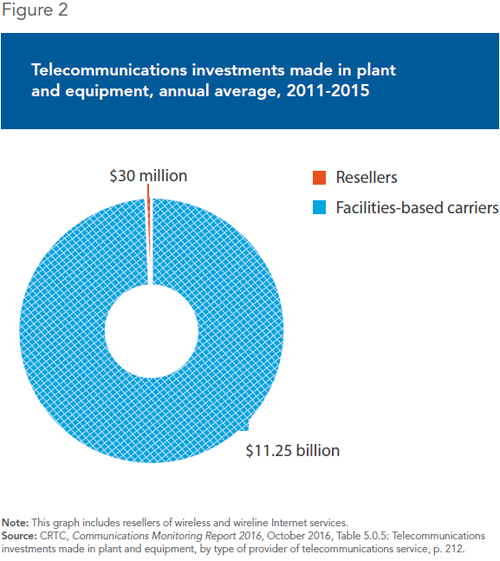

It is worth noting that resellers (of wireless as well as wireline Internet services) account for only a tiny fraction of all infrastructure investments made every year by telecommunications companies (see Figure 2). Not only do so-called “Wi-Fi first” resellers not invest anything in wireless infrastructure, but they also depend on the investments made by wireline Internet service providers for the Wi-Fi networks that their clients connect to.

Undermining the government’s fourth-player policy

As mentioned above, the federal government and the CRTC have over the past decade adopted several measures to encourage the emergence of a strong fourth wireless player in every region of the country. Taking the further step of artificially encouraging the multiplication of resellers would work against this policy.

These fourth wireless providers are still in the process of building and upgrading their networks and trying to gain market share. Resellers would compete more directly with them than with the three established national providers. As the CRTC noted in its ruling on this issue:

The new entrants have made and are planning to make significant investments in spectrum and their wireless networks. The Commission considers that mandating wholesale MNVO access at this time would significantly undermine these investments, particularly outside urban core areas.(11)

Increased regulatory uncertainty

Although the minister’s request refers only to “providers who offer service primarily over Wi-Fi,”(12) he acknowledged that there is “a lot of overlap” between Wi-Fi first carriers and MVNOs in general.(13) Indeed, broadening the definition of a home network to include the use of public Wi-Fi by the clients of a reseller would erase any logical distinction between resellers and wireless providers with their own infrastructure. As the CRTC itself noted, “there would be no way to distinguish between a company’s home network and every piece of network equipment in use by anyone in Canada.”(14)

Moreover, while Sugar Mobile offers its own application to make calls over a Wi-Fi connection, there is nothing special about this technology. There are an increasing number of Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) calling applications and services, such as Skype, WhatsApp, FaceTime, or Wi-Fi Calling, that can be used by anyone. For users who have a limited number of minutes in their plans, or often make international calls, they provide a way to avoid additional charges. And of course, most users regularly connect to Wi-Fi to upload and download data. For these reasons, “Wi-Fi first carrier” is actually a spurious category that should not constitute the basis for a regulatory change.

Seemingly conscious of the deleterious impact on investments of too broad a change in policy, the minister suggests that “impact on investment could be mitigated by imposing conditions on mandated wholesale roaming services” such as limits to the amount of roaming or a different wholesale rate.(15) But this would simply open the door, over the coming years and decades, to a series of rulings setting and re-evaluating these conditions on the basis of unworkable definitions. One way or another, a change of definition would, at a minimum, bring a lot of regulatory uncertainty, which is never good for investment.

Conclusion

More than a decade after the federal government issued a Policy Direction to the CRTC instructing it to “rely on market forces to the maximum extent feasible,”(16) it is now sending the opposite message by asking the regulator to undermine property rights, market forces, and sound competition, all while creating a new category of privileged players protected from competitive pressure, and making the regulatory regime more complex and uncertain. Canadian consumers will clearly be better served if the CRTC informs the minister, after reviewing his request, that it sees no need to modify its rules for wholesale roaming services.

References

1. See in particular Chapter 2 of the 2014 and 2016 editions of our Research Paper, The State of Competition in Canada’s Telecommunications Industry: “The Elusive Search for a Fourth Wireless Player” and “WINDs of Change in Canada’s Wireless Sector.”

2. There are several types of MVNOs that are more or less involved in the management of certain technical aspects of service provision. We are using the generic term “reseller” here to simplify the text.

3. For example, Videotron’s home network is in Quebec and Eastern Ontario.

4. Sugar Mobile was launched by Ice Wireless, a small telecom provider in northern Canada which has a roaming agreement with Rogers for when its clients leave the northern territories. However, Sugar Mobile’s clients are in southern Canada, outside of the home network of Ice Wireless. Rogers argued that its agreement with Ice Wireless did not allow Sugar Mobile clients to connect to its network because they did so permanently rather than incidentally. Sugar Mobile argued that this was not the case because its clients first connect to Wi-Fi networks. The CRTC ruled in favour of Rogers. See CRTC, Ice Wireless Inc. – Application regarding roaming on Rogers Communications Canada Inc.’s network by customers of Ice Wireless Inc. and Sugar Mobile Inc., Telecom Decision 2017-57, March 1, 2017.

5. Privy Council Office, Order in Council, PC Number: 2017-0557, June 1, 2017.

6. Ibid.

7. OECD, OECD Broadband Portal, Total fixed and wireless broadband subscriptions by country (June 2016), February 2017.

8. CRTC, Communications Monitoring Report 2016, October 2016, Table 5.5.15, p. 309.

9. Cisco, VNI Mobile Forecast Highlights 2016-2021, 2016. See Figures 1-1 to 1-4 in Martin Masse and Paul Beaudry, The State of Competition in Canada’s Telecommunications Industry – 2017, Research Paper, MEI, May 2017, pp. 10-13.

10. For a discussion of the benefits of facilities-based competition as opposed to service-based competition, see Martin Masse and Paul Beaudry, Chapter 4: “Facilities-Based Competition as a Spur to Innovation,” in The State of Competition in Canada’s Telecommunications Industry – 2016, Research Paper, MEI, May 2016, pp. 35-41.

11. CRTC, Regulatory framework for wholesale mobile wireless services, Telecom Regulatory Policy 2015-177, May 5, 2015, para. 121.

12. Privy Council Office, op. cit., endnote 5.

13. Rose Behar, “Minister Bains instructs CRTC to reconsider decision on mandated wholesale roaming,” mobilesyrup, June 5, 2017.

14. CRTC, Wholesale mobile wireless roaming service tariffs – Final terms and conditions, Telecom Decision 2017-56, March 1, 2017, para. 29.

15. Privy Council Office, op. cit., endnote 5.

16. Government of Canada, Order Issuing a Direction to the CRTC on Implementing the Canadian Telecommunications Policy Objectives, SOR 2006-355, December 14, 2006.