Should Super Nurses Be Allowed to Make Diagnoses?

Quebec’s Health Minister recently announced that she wanted specialized nurse practitioners (SNPs) to be able to make diagnoses, as is the case everywhere else in Canada. The Collège des médecins du Québec (CMQ) ended up making peace with the idea, while the Fédération des médecins omnipraticiens du Québec (FMOQ) is still not on board, claiming that this act must be reserved to physicians. Is this resistance justified?

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Pourquoi s’arrêter aux « super-infirmières »? (La Presse+, February 28, 2019)

Specialized nurses increase public access to care (Montreal Gazette, February 28, 2019) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Patrick Déry, Senior Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Health Policy Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and private initiative lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

Quebec’s Health Minister recently announced that she wanted specialized nurse practitioners (SNPs) to be able to make diagnoses, as is the case everywhere else in Canada. The Collège des médecins du Québec (CMQ) ended up making peace with the idea, while the Fédération des médecins omnipraticiens du Québec (FMOQ) is still not on board, claiming that this act must be reserved to physicians.(1) Is this resistance justified?

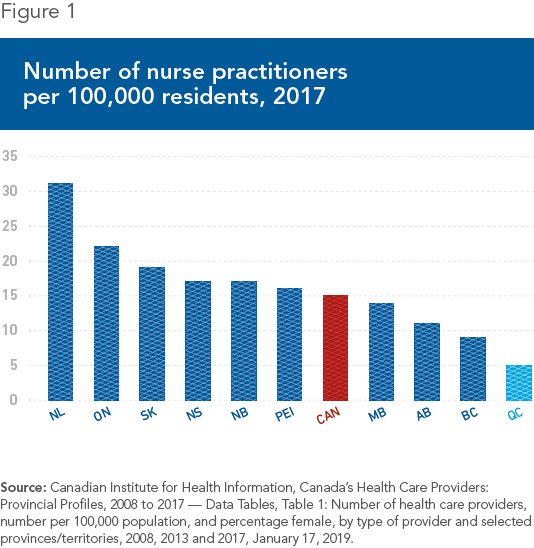

In all of Canada, Quebec is the place where there are the fewest super nurses as a proportion of the population. The province had barely 5 nurse practitioners per 100,000 residents in 2017, whereas the Canadian average was 15, and this same ratio was greater than 22 in Ontario (see Figure 1). The total number of nurse practitioners in Ontario last year was 3,300, versus 484 in Quebec.(2)

Yet it’s not as if the Quebec system was succeeding in meeting the demand for front line care. Quebec (and the rest of Canada, too) has few doctors compared to most industrialized countries.(3) One in five Quebecers still does not have access to a family doctor, and on the Island of Montreal, it’s one in three.(4) The province is also at the bottom of the pack among industrialized countries in terms of access to a consultation the same day or the next.(5) As for emergency wait times in Quebec, they are now legendary.(6) Expanding the scope of the work done by nurse practitioners would not solve every problem, but it would help improve this situation.

The Scientific Literature

Many studies have shown that nurse practitioners can provide a wide range of front line care—from 67% according to one Canadian study to 93% according to an American one. The American College of Physicians, for its part, concluded that from 60% to 90% of primary care can be provided by nurse practitioners.(7) One obvious advantage is to free up doctors from relatively simpler cases so that they can focus on those for which they have a particular expertise.

In addition to the quantitative argument, there is obviously the qualitative one to consider. A survey of some twenty studies carried out in OECD countries noted very high satisfaction rates on the part of patients having consulted nurse practitioners. One of these, conducted in nine clinics in the United States where nurse practitioners are well established, found that 91% of patients said they were “highly satisfied,” and 94% indicated an intention to return to the clinic.(8)

Patients’ impressions were corroborated by health indicators, which were found to be similar to those of patients treated by doctors. Notably, the longer consultations typically provided by nurse practitioners and the extra attention devoted to prevention led to improvements in certain indicators, particularly in the case of chronic diseases like diabetes. A reduction in wait times before accessing care and medication was also observed.(9)

A study that compared the decisions of nurse practitioners with those of physicians for 600 patients in the United Kingdom should reassure people who worry about possible frictions or divergence of opinions: Doctors and nurse practitioners agreed on 94% of diagnoses, and on 96% of treatments.(10)

Closer to home, a case study in British Columbia also showed how the arrival of nurse practitioners in a given region could significantly reduce wait times for getting an appointment. These went from one to six weeks when they arrived to three days or less in the space of just a few years, while the volume of patients treated was increasing. Over the same period, the number of emergency room visits for the same population of patients fell by around 40%. Finally, patients’ supply of available care increased, and they were able to choose their health professional for a given visit.(11)

To the conclusions of all these studies can be added the fact that the training of nurse practitioners involves more hours of instruction in Quebec, both theoretical and clinical, than elsewhere in Canada.(12)

For Better Access to Care

While the question of diagnoses for everyday health problems and certain chronic diseases has now been resolved, some barriers remain, and Quebecers still don’t have access to the full range of nurse practitioners’ skills.(13) Why is this the case, given that Canadian and international experience shows that there is no good reason for it?

Beneath the argument of “protecting the public,” there is in fact a good dose of groups protecting their interests. The restrictions imposed on nurse practitioners in Quebec are a typical example of regulatory capture in favour of a small group (medical doctors, through certain groups that represent them), to the detriment of the Quebec population as a whole.

The Health Minister is right to want to remove these barriers. The same spirit of openness should apply to all health professionals, in order to allow them to use all their skills, even if these sometimes overlap. For example, we could apply the same reasoning to pharmacists or to dental hygienists; Quebec is again an outlier in prohibiting the former from administering vaccines, and the latter from practising their profession without the supervision of a dentist.(14) In sum, the point is not to pit health professionals against one another, but to ensure the best possible access to care.

References

1. Radio-Canada, “Les superinfirmières en renfort pour désengorger le réseau de la santé,” February 18, 2019; Janie Gosselin, “Volte-face du Collège des médecins,” La Presse+, February 24, 2019; Ariane Lacoursière, “Les IPS pourront poser des diagnostics dès aujourd’hui,” La Presse+, February 26, 2019.

2. College of Nurses of Ontario, What is CNO? Nursing Statistics, Data Query Tool; Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers du Québec, Rapport statistique sur l’effectif infirmier 2017-2018 – Le Québec et ses régions, 2018.

3. Patrick Déry, “It’s Time to End Med School Quotas,” Viewpoint, MEI, March 15, 2018.

4. Quebec Department of Health and Social Services, Professionnels, Statistiques et données sur les services de santé et de services sociaux, Accès aux services médicaux de première ligne, Données sur l’accès aux services de première ligne.

5. Quebec Health and Welfare Commissioner, Perceptions et expériences de la population : le Québec comparé, Résultats de l’enquête internationale du Commonwealth Fund de 2016, February 2017, p. 16.

6. Patrick Déry, “Quebec Hospitals Require Entrepreneurship,” Viewpoint, MEI, July 12, 2018.

7. Claudia B. Maier et al., “Descriptive, cross-country analysis of the nurse practitioner workforce in six countries: size, growth, physician substitution potential,” BMJ Open, Vol. 6, No. 9, September 6, 2016.

8. Marie-Laure Delamaire and Gaétan Lafortune, Nurses in Advanced Roles: A Description and Evaluation of Experiences in 12 Developed Countries, OECD, August 31, 2010, p. 43.

9. Marie-Laure Delamaire and Gaétan Lafortune, ibid., pp. 43-50.

10. Marie-Laure Delamaire and Gaétan Lafortune, ibid., p. 46.

11. Alison Roots and Marjorie MacDonald, “Outcomes associated with nurse practitioners in collaborative practice with general practitioners in rural settings in Canada: A mixed methods study,” Human Resources for Health, Vol. 12, No. 69, December 11, 2014, p. 6.

12. Association des infirmières praticiennes spécialisées du Québec, Formations requises.

13. For example, they still cannot refer a patient to a specialist. AIPSQ, “Mémoire de l’Association des infirmières praticiennes spécialisées du Québec (AIPSQ) présenté à l’Office des professions du Québec,” May 2017.

14. Canadian Pharmacists Association, Pharmacy in Canada, Pharmacists’ Expanded Scope of Practice; Isabelle Ducas, “Soins dentaires : des soins plus abordables avec des hygiénistes autonomes,” La Presse+, February 9, 2016.