Relying on Entrepreneurs to House and Care for Our Seniors

It seems that each week brings its share of bad news about the Quebec health care system, to the point that we forget that certain of its components work rather well. This is the case for senior housing and care, largely provided by the private sector.

Media release: Seniors’ housing: Quebec needs entrepreneurs

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Les aînés bien logés et soignés grâce au privé (Le Soleil, April 26, 2018)

CHSLD : le privé dans le public, ça fonctionne (The MEI’s Journal de Montréal blog, May 10, 2018) CHSLD : pourquoi le privé fait-il mieux? (The MEI’s Journal de Montréal blog, May 14, 2018) |

Interview (in French) with Patrick Déry (Mario Dumont, LCN-TV, April 26, 2018) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Patrick Déry, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Health Policy Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and private initiative lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

It seems that each week brings its share of bad news about the Quebec health care system, to the point that we forget that certain of its components work rather well. This is the case for senior housing and care, largely provided by the private sector.

Private residences make up over two thirds of senior housing spaces in Quebec. They serve autonomous and semi-autonomous seniors. For those for whom a stay in residence is not feasible because of their greater needs, the government subsidizes a network of long-term care facilities (CHSLDs), either fully public or privately run (“private funded”),(1) which represent a quarter of total housing spaces.(2) But the government and the market respond very differently to the pressures of an aging population.

The Grey Wave

Last December, the Health and Welfare Commissioner, in his final report before his position was abolished, noted that a little over 2,400 people aged 75 and over were waiting for a housing space in a public CHSLD. From 2010-2011 to 2016-2017, while the population aged 75 and older increased by 15% in Quebec, the number of beds in these facilities fell from 38,394 to 37,468, a reduction of 2.4%.(3)

The average wait, specifically the time spent on the waiting list since requesting housing, was ten months in 2016-2017. In certain regions of Quebec, it can reach 15 months. This is a long time when you consider that the average length of stay in a CHSLD is 27 months.(4)

Even though only 4.4% of people aged 75 and over currently live in a CHSLD, they account for two thirds of the beds.(5) By 2031, it is expected that the population in this age category will practically double.(6) Under current conditions, the shortage of spaces in the public system will likely get worse, especially given that the government tends to react slowly to an increase in the demand for care.(7)

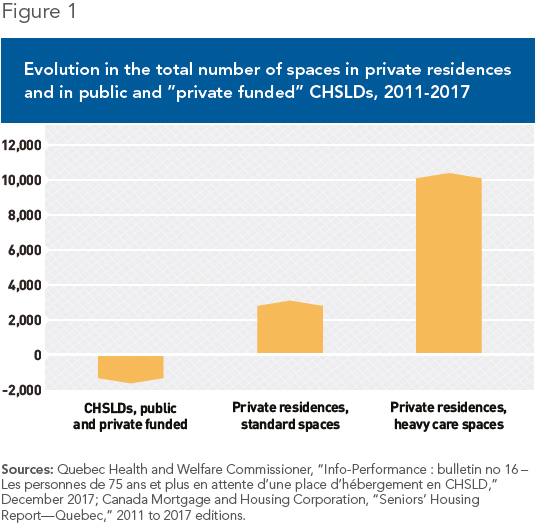

The picture is quite different in the private sector. According to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, the number of standard spaces in seniors’ residences in Quebec(8) grew from 90,309 to 93,351 between 2011 and 2017, with an average vacancy rate of 7.6% for the period. The number of heavy care spaces, which serve a clientele requiring at least an hour and a half of care per day, increased even more rapidly: It grew from 3,469 to 13,800, and the vacancy rate was 5.2%.(9) This means that, contrary to public CHSLDs, the seniors’ residences market adjusted to the growing demand for senior housing and care (see Figure 1).

Quebec is the province with the most private senior housing spaces, proportional to its population. This more developed market also happens to feature the lowest rents in the country.(10)

Studies(11) have shown that, contrary to certain misperceptions,(12) the quality of care is high in private residences in Quebec, and it tends to improve over the years. A recent poll indicates that users are largely satisfied: The overall satisfaction rate, which is 94%, climbs to 98% when it comes specifically to care.(13)

Entrepreneurship in the Public System

Even within the subsidized CHSLD system, it is possible to benefit from entrepreneurial dynamism. Indeed, of the 432 CHSLDs funded directly by the government, 62 are private, so-called “funded” facilities that are run by entrepreneurs.(14) These facilities do not have more resources than the CHSLDs run by the government, but nonetheless manage to generate a profit. The clientele and the cost of housing are the same as for fully public CHSLDs, they are accessed through the same regional portal, and the working conditions are the same. In practice, from the point of view of the user, private funded CHSLDs are perfectly integrated into the public system—with two important differences.

The first is financial: If there are unused funds in the clinical portion of the funding (the part devoted specifically to care), they must be returned to the government. And since these are private companies, private funded CHSLDs have to pay taxes.

The second difference has to do with the patients. A recent compilation of evaluation visits carried out by the Department of Health in nearly half of Quebec’s CHSLDs showed that the overall quality of the facilities and of the care provided was higher in private funded facilities. Among these, 70% had been evaluated by the department as providing a “very adequate” living environment, versus just 17% of fully public CHSLDs. No private funded CHSLD was “of concern,” versus 15% of CHSLDs run by the government.(15)

Conclusion

Entrepreneurial dynamism already meets the needs of tens of thousands of seniors housed in private residences in Quebec, and the growing demand for this care. The government should not hesitate to draw on this same dynamism by relying on private funded CHSLDs in the future development of the public system. Their quiet success shows how entrepreneurship can deliver better care at a lower cost for the government, all while maintaining accessibility.

References

1. Fees for public and private funded CHSLDs are subsidized. It is also possible to request a reduction or even an exemption of fees. See Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec, Aid programs, Accommodation in a public facility.

2. The remaining spaces, some 7%, are private unfunded CHSLDs and intermediate and family-type resources, which are also private. See Yanick Labrie, The Other Health Care System: Four Areas Where the Private Sector Answers Patients’ Needs, Research Paper, MEI, March 31, 2015, pp. 9-17.

3. Quebec Health and Welfare Commissioner, “Info-Performance : bulletin no 16 – Les personnes de 75 ans et plus en attente d’une place d’hébergement en CHSLD,” December 2017.

4. Idem.

5. Idem.

6. On July 1st, 2017, there were 664,000 people aged 75 and over in Quebec. This figure is expected to climb to 1.21 million by 2031. See Institut de la statistique du Québec, Le bilan démographique du Québec, Édition 2017, December 12, 2017, p. 26; Institut de la statistique du Québec, Perspectives démographiques du Québec et des régions, 2011-2061, Édition 2014, September 9, 2014, p. 111.

7. For example, a new CHSLD with 99 spaces, announced in February 2018, will only open its doors in 2022, and will add only 16 new spaces in all. See Government of Quebec, “Nouveau centre d’hébergement et de soins de longue durée à Lac-Mégantic,” Press release, February 19, 2018.

8. In residences in which at least 50% of residents are aged 65 and over, and in which not all residents receive heavy care.

9. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Housing Market Information Portal, Seniors’ Rental Housing; Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, “Seniors’ Housing Report—Quebec,” 2011 to 2017 editions.

10. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Housing Market Information Portal, Seniors’ Rental Housing.

11. Yanick Labrie, op. cit., endnote 2.

12. Dominique Scali, “Peu de confiance dans les résidences privées,” Le Journal de Montréal, September 14, 2015.

13. Leger, Étude de satisfaction – Sondage auprès des personnes âgées des résidences membres du RQRA, Poll carried out on behalf of the Quebec Seniors’ Housing Group (QSHG), June 2017.

14. Access to information request, April 2018. This total does not include private unfunded CHSLDs with government purchase agreements for spaces.

15. Quebec Department of Health and Social Services, Visites ministérielles d’évaluation de la qualité de vie en CHSLD, Bilan statistique national, Period from April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016, July 2016. 25% of private unfunded CHSLDs were qualified as “very adequate” and 13% as “of concern.”