Schumpeter: Entrepreneurship in the service of innovation

Op-ed published exclusively on our website.

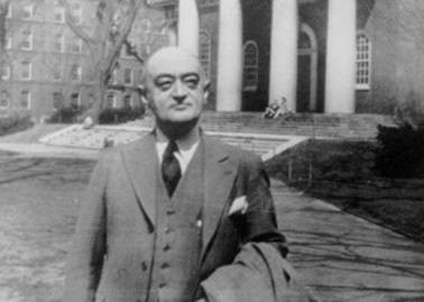

Contrary to many economists who spend most of their lives at university, Joseph Alois Schumpeter had an adventurous life, including a variety of professional activities carried out on several continents. Born in 1883, the Austrian was ambitious. He claimed to have set as goals to become the best economist in the world, the best horseman in Austria, and the greatest lover in Vienna—and to have achieved two out of the three!

Over the course of his life, he worked as a lawyer, a finance minister, a banker, a teacher, and a writer. These multiple experiences, as well as his interest in sociology and politics, made him an uncommon thinker who left behind a considerable body of work, including Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy and the posthumous History of Economic Analysis.

While Schumpeter studied in Vienna under the auspices of some of the most brilliant economists of their generation like Wieser and Böhm-Bawerk, he is considered more of an unclassifiable economist than a representative of the Austrian School. He does not share with that school the idea that socialism is unworkable, and he accords a larger place to history in the explanation of economic mechanisms. He is nevertheless an essential thinker whose work remains relevant, mainly for two ideas that revolutionized economics.

First, there is the role of innovation and entrepreneurs in explaining economic development. Schumpeter distinguishes the entrepreneur both from the rentier whose income is due to speculation alone and from the heir whose fortune is due to parentage. The entrepreneur, in contrast, discovers new ideas, swims against the current, breaks the routine, and innovates by finding new ways of producing.

For Schumpeter, who was also a sociologist, the lure of profit is not the only thing that motivates entrepreneurs. They are first and foremost animated by an adventurous spirit and seek out the sensation of conquest and discovery. The innovations they create change the lives of thousands of people. Their profit is legitimate, as it serves to reward the risks they take. It is entrepreneurs who are the motor of growth in a competitive economy, not government policies.

Second, Schumpeter left his mark on the history of economic thought with his theory of business cycles dominated by the phenomenon of innovation. The process of economic growth is punctuated by episodes of routine and moments of rupture marked by the generalized destruction of businesses in certain sectors. These are then replaced by new economic actors who organize new production techniques.

Indeed, big inventions like the steam engine and electricity were accompanied by clusters of innovations that turned the whole economy on its head. Often denounced, these moments of upheaval are actually good things. For one thing, innovation spreads and benefits society as a whole. For another, economic activity is actually displaced. The job destruction and decreased activity in one sector are offset by job creation and increased activity in a new, innovative sector. This is the well-known theory of “creative destruction” that made this Austrian professor famous.

This theory was useful in its day for understanding the changes that accompanied the Industrial Revolution. It is just as useful today for understanding the transformations accompanying the digital revolution that is taking place before our eyes. Entrepreneurs have, over the past decades, succeeded in transforming a scientific discovery in the field of computing into a cluster of innovations that improve our lives on a daily basis.

These changes lead some to say that robots and computers are taking our jobs. But recent studies prove Schumpeter right: Innovations in the fields of computing, robotics, and communications merely transfer jobs from certain sectors to others and are beneficial to the entire population overall.

Finally, Schumpeter’s work is also striking in its analysis of society and politics. Pessimistic by nature, he predicted the inevitable disappearance of capitalism and its replacement by socialism due to the growing hostility of entire segments of the population to this system. Among these he included intellectuals, who had become masters in the art of contesting the system that allowed them to express themselves freely and to enjoy a certain level of comfort.

Fortunately, the professor’s pessimistic predictions did not come true, and socialism collapsed at the end of the 20th century. But his sociological analysis of the paradoxical resentment of certain groups toward the market economy remains relevant. One need only think of the anti-globalization crowd planning the next revolution using smartphones, tablets, and other products of the very economic system they denounce.

Jasmin Guénette is Vice President of Operations at the Montreal Economic Institute. The views reflected in this op-ed are his own.

____________________

Read more articles on the theme of Theory, History and Thinkers.