It’s Time to End Med School Quotas

Quebec’s Health Minister announced a reduction in the number of medical school admissions last year in order to keep doctors from ending up unemployed in the future. And yet, one in five Quebecers still does not have a family doctor, and proportionally, Quebec has fewer doctors than most industrialized countries. Is this government control over access to medical training the best way to meet Quebecers’ health care needs?

Media release: Yes, Quebec does lack doctors

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Y a-t-il vraiment trop de médecins au Québec? (La Presse+, March 15, 2018)

Slashing Med School Admissions Isn’t How You Deal With A Doctor Shortage (Huffington Post, March 19, 2018) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Patrick Déry, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Health Policy Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and private initiative lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

Quebec’s Health Minister announced a reduction in the number of medical school admissions last year in order to keep doctors from ending up unemployed in the future.(1) In Quebec, it is the government that decides how many medical students universities can admit for the next three years.(2)

And yet, one in five Quebecers still does not have a family doctor,(3) and proportionally, Quebec has fewer doctors than most industrialized countries. Is this government control over access to medical training the best way to meet Quebecers’ health care needs?

“Too Many” Doctors? Not Really

International comparisons show that in Quebec, it is particularly difficult to see a physician when you need to. In a survey comparing patient responses in 11 countries, including Canada, Quebec is last in terms of access to a doctor or a nurse the same day or the following day, last in terms of access to a specialist within four weeks, last in terms of wait times for elective surgery, and unsurprisingly, dead last for emergency wait times.(4) Moreover, a poll carried out in 2017 showed that Quebecers think that access to a family doctor and emergency wait times should be the top priority of politicians.(5)

Yet a widespread notion that regularly finds its way into news reports is that the province has a lot of doctors. The current Health Minister has even said that the province has “about 10%” too many doctors, or around 2,000 of them.(6) What are the facts?

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, Quebec had 2.43 doctors per 1,000 inhabitants, which is slightly higher than the Canadian average (2.3). Nova Scotia (2.58) is the province with the most doctors, while Saskatchewan (1.97) is the one with the fewest. Quebec has somewhat more doctors than Ontario (2.2), and just barely more than British Columbia (2.42) and Alberta (2.41).(7)

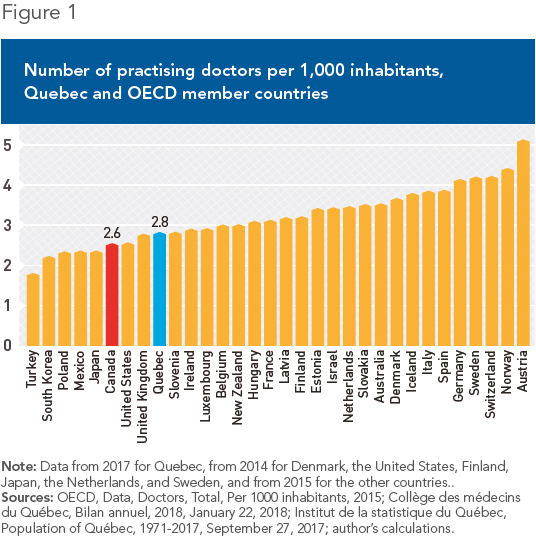

The picture looks quite different when we compare Quebec’s medical workforce with that of other industrialized countries. By using the OECD’s definition of “practising doctors,” which includes residents but excludes physicians who have no direct contact with patients, we observe that Quebec has 2.8 doctors per 1,000 inhabitants, which is less than most industrialized countries (see Figure 1).

In this comparison of some thirty countries, only Turkey, South Korea, Poland, Mexico, Japan, and the United States have proportionally fewer doctors than Quebec. The United Kingdom has almost as many, but since the number of graduates in medicine is higher, it is only a matter of time before it moves ahead.(8)

Still according to the OECD’s criteria, Quebec currently has around 23,605 practising physicians.(9) If it had the same ratio as Australia, namely 3.5 doctors per 1,000 inhabitants, it would have around 6,000 doctors more, some 11,000 more if it had as many as Germany (4.1), and nearly 20,000 more if it had as many as Austria (5.1). It is easy to imagine that the problem of access to health care would not be as acute if this were the case.

Benefits for Patients

Increasing the number of doctors would be beneficial in several ways. First, the public system would have a larger workforce from which to fill vacant positions, which currently number in the hundreds.(10) Access and patient choice would increase correspondingly. Also, this would allow unaffiliated private clinics to develop without any risk (real or perceived) of them cannibalizing the public system. The growing demand for care and the chronic inability of the public system to satisfy it are business opportunities for entrepreneurs. For example, one doctor already owns seven private clinics and plans to have between 25 and 50 within five years.(11)

Thus, if the government continues to ration care and limit access as it does at present, new doctors will have the option of working outside the public system and continuing to increase the overall supply of care, without affecting the supply in the public sector. This is indeed what Quebecers want.(12) More competition in the supply of care will only be beneficial for patients.

Oxygen to the System

For years, the Quebec Health Department has tried unsuccessfully to predict the needs of Quebecers by calculating, ten years ahead of time, the number of doctors that will be required to meet those needs. This exercise rests on the premise that an all-powerful central authority can possess all the necessary information about the future intentions of millions of patients and tens of thousands of health professionals. The experience of the past thirty years shows that this is a fantasy.(13)

Concretely, year after year, the government just ends up having too few doctors and making patients wait. Doing away with artificial and arbitrary medical school enrolment quotas and allowing all those with the ability to study medicine to do so would inject a much-needed supply of oxygen into Quebec’s health care system. It could then evolve in response to the needs of patients, instead of according to the dictates of bureaucrats and politicians.

References

1. Hugo Duchaine, “Gaétan Barrette coupe le nombre de futurs médecins,” Le Journal de Montréal, July 8, 2017.

2. Government of Quebec, “Politique triennale des nouvelles inscriptions dans les programmes de formation doctorale en médecine et du recrutement de médecins sous permis restrictif pour 2016-2017, 2017-2018 et 2018-2019,” Document obtained through a request for access to information, February 2018.

3. Caroline Touzin, “Accès à un médecin de famille : Québec s’éloigne de sa cible,” La Presse, March 10, 2018.

4. Quebec Health and Welfare Commissioner, Perceptions et expériences de la population : le Québec comparé, Résultats de l’enquête internationale du Commonwealth Fund de 2016, February 16, 2017, pp. 16, 20, 21, and 43.

5. Léger, “La politique au Québec,” May 20, 2017, p. 21.

6. “Le Québec ne manque pas de médecins,” Radio-Canada, September 28, 2017; Régys Caron, “Le Québec compte un surplus de 2000 médecins, affirme le ministre Barrette,” Le Journal de Montréal, September 30, 2016.

7. Canadian Institute for Health Information, Physicians in Canada, 2016: Summary Report, 2017, p. 22.

8. In Quebec, there are around 10.5 medical school enrolments per 100,000 in habitants, whereas the United Kingdom has 12.8 medical graduates per 100,000 inhabitants. Fédération médicale étudiante du Québec, Les effectifs médicaux au Québec : Un médecin pour chacun et une place pour chaque médecin, March 2017, p. 7; OECD, “Medical graduates,” in Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, November 10, 2017.

9. Since the number of practising physicians is not available for Quebec, the gap between professionally active doctors and those in practice was estimated using the data for Canada. OECD iLibrary, OECD Health Statistics, Health care resources, Health employment and education, Physicians; OECD Health Statistics 2017, Definitions, Sources and Methods, Practising physicians.

10. François Cormier, “Médecins spécialistes : 545 postes vacants au Québec,” TVA Nouvelles, February 5, 2018.

11. Hugo Duchaine, “Il veut être le Jean Coutu des cliniques privées,” Le Journal de Montréal, January 31, 2018.

12. Pôle santé HEC Montréal, Des idées en santé pour le Québec, April 2017, p. 80.

13. Germain Belzile and Jasmin Guénette, “Centralized Health Care: A Recipe That’s Doomed to Fail,” Viewpoint, MEI, July 13, 2017.