Transiting to Privatization

Over the past few decades, the costs of public transit in Montreal have outpaced services rendered. This occurred while many municipalities around the world opted to reform their public transit systems by increasing the involvement of the private sector. This Economic Note provides an overview of the history of public transit in Montreal and of international experiences with private involvement.

Media release: The Montreal metro’s golden anniversary: Time to part ways with an outdated model

Links of interest

Links of interest

|

|

|

|

Privatizing, partnerships future of public transit (Toronto Sun, October 14, 2016)

En commun vers le changement ! (The MEI's Journal de Montréal blog, October 18, 2016) STM : ouvrons-nous au secteur privé (La Presse+, November 20, 2016) |

Interview (in French) with Germain Belzile (Dutrizac, 98,5 FM, October 14, 2016)

Interview (in French) with Vincent Geloso (100% Normandeau, blvd 102.1 FM, October 14, 2016) |

Report (in French) with Vincent Geloso (Le TVA 22 h, October 13, 2016)

Interview (in French) with Germain Belzile (Mario Dumont, LCN TV, October 14, 2016) |

Transiting to Privatization

Over the past few decades, the costs of public transit in Montreal have outpaced services rendered. This occurred while many municipalities around the world opted to reform their public transit systems by increasing the involvement of the private sector. This Economic Note provides an overview of the history of public transit in Montreal and of international experiences with private involvement.(1)

Disappointing Historical Performance

The provision of public transit was not always in the realm of the public sector.(2) It was only in the decades after World War II that more cities began to socialize the provision of public transit.(3) Most North American cities had profitable and privately owned transit systems until the 1960s, when governments started providing financial incentives for cities to take over.(4) Montreal was one of the early adopters, municipalizing the Montreal Tramways Company in 1951, today called the Société de transport de Montréal (STM).(5)

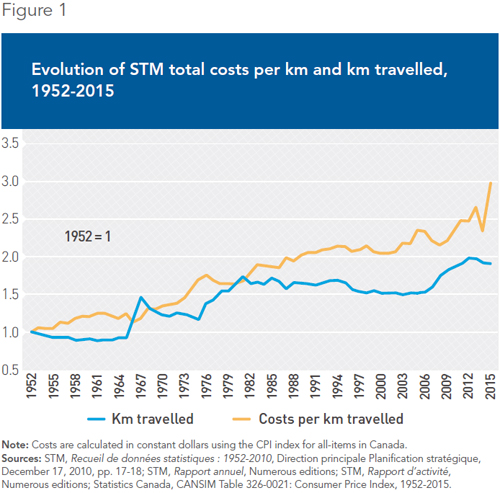

Since then, the performance of that public monopoly has been quite disappointing. Between 1952 and 2015, inflation-adjusted total costs increased by 470%, while the number of kilometres travelled increased by only 91%, so that the cost per kilometre travelled increased by 198%.(6)

Even limited to the era of the subway—which represents a large, permanent increase in costs—this remains true. Since the introduction of Montreal’s metro system in 1966, inflation-adjusted total costs increased by 314%, while kilometres travelled increased only 57%, leaving a per km travelled cost increase of 163%. Figure 1 illustrates how the growth in costs per km has accompanied the growth in kilometres travelled.

This increase in costs was not accompanied by increases in the reliability of the service—at least not in recent decades. Data regarding major delays in subway services are available only starting in 1983 when there were 6.3 delays per million km travelled.(7) In 2015, that proportion had risen to 12.2 delays per million km travelled.(8)

In contrast, even the flawed pre-municipalized system operated by a regulated private monopoly managed to control costs better while expanding services. According to the details contained in the archived Annuaire statistique du Québec, costs per kilometer travelled fell 17% between 1933 and 1950 while distance travelled increased 61%.(9)

Furthermore, the STM’s costs are paid by riders and non-riders alike. Prior to municipalization, the city collected taxes from the private operator, which had to raise revenues solely from its own operations. In the early days of public provision, this remained largely the case, with more than 90% of the STM’s revenues coming from ticket sales until 1971.(10) Thereafter, the public treasury became an increasingly significant source of revenue for the operation of transit services in Montreal.

At present, just 46% of all of the STM’s operating revenues are own-source revenues. That leaves Montreal and Quebec taxpayers on the hook for $659 million a year.(11) The STM also receives an additional $744 million in subsidies for its investment budget. This represents a large financial burden covered by taxpayers, despite the fact that the inflation-adjusted fare (the price of a single ticket) has increased by 272% since 1952, and by 45% just since 2000.(12)

Alternatives to Public Management

Elsewhere, as in Montreal, public operation and heavy subsidization of transit services have led to rising costs and prices, and falling productivity, which partly explains the waning popularity of public transit.(13) This is hardly surprising. In the absence of competition, there are very few incentives for a monopoly to improve performance, especially when it is heavily subsidized. Since it disconnects a firm’s revenues from its clientele’s willingness to acquire its services, subsidization encourages financial mismanagement, a lack of initiative, and reduced productivity.(14)

In addition, public corporations do not face the same pressures as private firms. Since political and economic interests do not necessarily align, these pressures may lead to the satisfaction of political needs.(15) Managers of public transit authorities face pressure from unions and local political leaders, and may thus be more inclined to establish inefficient bus routes, for example, or hire more workers than needed at wages above the market level. The net effect is higher average costs per kilometer of transit service. These costs are passed on either directly to consumers through higher fares or indirectly to taxpayers through higher taxes.

The unimpressive results of public ownership have pushed many governments to shift gears and adopt new approaches that rely on private involvement. Over the past four decades, this involvement has taken many different forms depending on the depth of activities delegated to the private sector. In some cases, both the planning of the routes and their operation were delegated to the private sector—which means that the service was privatized and opened up to competition. Local bus services outside London in the United Kingdom are an example of such an approach.

Other governments decided not to resort to outright privatization, simply delegating certain portions of their activities to private firms. This occurs though competitive bidding on certain transit activities ranging from maintenance services to the operation of certain routes. Bus contracts tend to be awarded for fixed periods of time with certain constraints and requirements regarding fares and timetables. Such forms of private involvement have been implemented in France, Australia, New Zealand, and Sweden, in the city of London, and in many American cities. The suburbs around Montreal have also opted for competitive tendering, with intermunicipal boards of transport awarding contracts to private companies to run bus services.(16)

Outcomes of Private Involvement

These alternatives to full public management offer a number of advantages. The largest is that private firms are under constant pressure from shareholders to improve performance. Under such pressures, there are incentives to control costs, improve efficiency, and respond rapidly to changing market conditions. While the transition to greater private involvement can be challenging, the results are generally positive.(17)

The United Kingdom was the first country to experiment extensively with private involvement in urban transit, in the 1980s. Outside London, urban bus services were privatized and competition was permitted. Within the city, the operation of bus lines was delegated to the private sector through competitive tendering. The new operators switched to more appropriate vehicles based on the popularity of different routes. They also made substantial investments in fuel efficiency technologies, and reduced their workforces and their labour costs without cutting wages.

Thanks to these reforms, costs per vehicle-kilometre fell dramatically. For the United Kingdom outside of London, this reduction was most pronounced up to the end of the 1990s (see Figure 2). Thereafter, operating costs have increased slightly. However, this modest increase was largely the results of growing fuel costs.(18)

For London, inflation-ajusted operating costs per vehicle-kilometre fell by 28% between 1985-86 and 2008-09. The reforms were accompanied by substantial reductions in subsidies to local bus providers until the early 2000s, while service increased.(19) Even seemingly disappointing cases of reform in the United Kingdom—like the city of Hereford, where one firm managed to dominate the market after a few years of competition—are encouraging.(20) In this case, after a protracted price war, fares returned to their initial levels, but service levels remained substantially higher than prior to the reform.(21)

In the United States, the city of Indianapolis achieved similar results. In the 1990s, the city switched to a tendering system for a large number of its bus routes. This switch halted and reversed the decline in ridership, showing that the waning popularity of public transit was partly the result of inept public management. In addition, the reform led to annual reductions of 2.5% in operating costs.(22)

An extensive survey of 800 transit agencies in the United States revealed that over a third of them had switched to competitive tendering, leading to cost reductions ranging from 10% to 50%.(23) A more recent study surveyed 328 American transit agencies between 1998 and 2011 and found that 43% of them resorted to private involvement. On the basis of comparisons that this data allowed, full privatization was estimated to reduce operating costs per kilometre by 70%. In terms of overall costs, these savings represented a 30% reduction in total US bus transit expenses.(24)

Lessons for Montreal

The experience of Montreal stands in stark contrast with foreign experiments with private involvement in urban transit. In order to move forward, the option of competitive tendering should at the very least be considered, with the municipal government determining the desired service and then allowing private firms to handle operations. Buses would be an ideal starting point, as the city could follow the well-documented reforms applied in London.

These reforms can be accomplished, and their full benefits realized, without jeopardizing the working conditions of current employees. In 2015 alone, 12% of STM employees were eligible for retirement.(25) A plan to permit gradual private involvement for buses would allow a reduction of the workforce through attrition. In addition to a better use of capital, this could lead to significant reductions in operating costs, and urban transit subsidies could gradually be eliminated.

This Economic Note was prepared by Germain Belzile, Senior Associate Researcher at the MEI, and Vincent Geloso, Associate Researcher at the MEI.

References

1. The MEI published an Economic Note on this topic in August 2004. The current Note updates the state of the situation.

2. Matthew Karlaftis and Patrick McCarthy, “The Effect of Privatization on Public Transit Costs,” Journal of Regulatory Economics, Vol. 16, No. 1, July 1999, p. 27.

3. Kenneth A. Small and Erik T. Verhoef, The Economics of Urban Transportation, 2nd Ed., Routledge Press, 2007, p. 203.

4. Randal O’Toole, Fixing Transit: The Case for Privatization, Cato Institute, November 2010, pp. 2-3.

5. STM, Company timeline, Commission de Transport de Montréal (1951-1969).

6. The year 1952 is the earliest year for which this data is available. STM, Recueil de données statistiques : 1952-2010, Direction principale Planification stratégique, December 17, 2010, pp. 17-18; STM, Rapport annuel, Numerous editions; STM, Rapport d’activité, Numerous editions; Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 326-0021: Consumer Price Index, 1952-2015.

7. STM, Recueil de données statistiques : 1952-2010, Direction principale Planification stratégique, December 2010, pp. 17 and 45.

8. STM, Rapport annuel 2015, April 7, 2016, pp. 11 and 20.

9. Quebec Department of Commerce and Industry, Annuaire statistique du Québec, 1934 and 1952. The data before 1952 is not compatible with the subsequent data. Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 326-0021: Consumer Price Index, 1933-1950.

10. STM, op. cit., endnote 7, p. 26.

11. STM, op. cit., endnote 8, p. 65.

12. This is the unit price when purchasing a booklet of 6 tickets in 1952 and 2000, and 10 tickets in 2015. STM, op. cit., endnote 7, p. 29; STM, Rapport annuel 2001, January 1, 2002, p. 14; STM, “Tarifs 2015: bus et métro,” 2015; Statistics Canada, op. cit., endnote 6.

13. Randal O’Toole, op. cit., endnote 4, pp. 3-7; Clifford Winston, “Government Failure in Urban Transportation,” Fiscal Studies, Vol. 21, No. 4, December 2000, pp. 403-425.

14. Matthew Karlaftis, “Privatisation, Regulation and Competition: A Thirty-Year Retrospective on Transit Efficiency,” in Privatisation and Regulation of Urban Transit Systems, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and International Transport Forum, 2008, p. 73; Aidan Vining and Anthony Boardman, “Ownership versus Competition: Efficiency in Public Enterprise,” Public Choice, Vol. 73, No. 2, 1992, pp. 205-239.

15. Gordon Tullock, “People Are People: The Elements of Public Choice,” in Gordon Tullock (ed.), Government Failure: A Primer in Public Choice, Cato Institute, 2002, pp. 3-16.

16. Transport Canada, “The Private Sector and Public Transit Service in Canada,” Case Study 36, May 2005, p. 2.

17. Kenneth A. Small and Eric T. Verhoef, op. cit., endnote 3, p. 208.

18. United-Kingdom Department of Energy and Climate Change, Typical January retail prices of petroleum products, February 25, 2016.

19. Subsidies began to increase again substantially in the early 2000s. John Preston and Talal Almutairi, “Evaluating the Long Term Impacts of Transport Policy: An Initial Assessment of Bus Deregulation,” Research in Transportation Economics, Vol. 39, No. 1, March 2013, pp. 210-213.

20. John Hibbs, The Dangers of Bus Re-regulation and Other Perspectives on Markets in Transport, Institute of Economic Affairs, October 2005, p. 43.

21. Andrew Evans, “Hereford: A Case-Study of Bus Deregulation,” Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, Vol. 22, No. 3, September 1988, pp. 283-306.

22. Matthew Karlaftis and Patrick McCarthy, op. cit., endnote 2, pp. 27-43.

23. Matthew Karlaftis, op. cit., endnote 14, p. 85.

24. Rhiannon Jerch, Matthew E. Kahn, and Shanjun Li, Efficient Local Government Service Provision: The Role of Privatization and Public Sector Unions, Working paper 22088, National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2016.

25. STM, op. cit., endnote 8, p. 13.