Viewpoint – NAFTA: Donald Trump’s Criticisms Are Unfounded

The Republican Party’s presumptive nominee for the presidency of the United States, Donald Trump, has made the negative effects of the opening up of borders, and especially of trade between the United States and Mexico, one of his recurring themes. He claims that free trade does not benefit the United States. According to him, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is “a disaster” that needs to be renegotiated. In Canada, this opposition to free trade finds a certain echo among commentators and lobby groups. The truth of the matter, though, is that this agreement has had positive effects for the three countries involved.

Media release: Donald Trump off target in rejecting NAFTA

Links of interest

Links of interest

|

|

|

|

Le libre-échange: Trump nous trompe (Le Devoir, July 13, 2016)

Trump’s anti-NAFTA myths are catching on in Canada, unfortunately (National Post, July 14, 2016) |

Viewpoint – NAFTA: Donald Trump’s Criticisms Are Unfounded

The Republican Party’s presumptive nominee for the presidency of the United States, Donald Trump, has made the negative effects of the opening up of borders, and especially of trade between the United States and Mexico, one of his recurring themes. He claims that free trade does not benefit the United States.(1) According to him, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is “a disaster” that needs to be renegotiated. In Canada, this opposition to free trade finds a certain echo among commentators and lobby groups. The truth of the matter, though, is that this agreement has had positive effects for the three countries involved.

The Effects of NAFTA

The liberalization of trade brings lasting benefits at the cost of certain short-term inconveniences. This is one of the uncontestable conclusions of economic analysis, agreed upon by practically all economists. Free trade increases well-being in the countries concerned thanks to falling prices and efficiency gains, despite the initial disappearance of certain jobs at less efficient companies that produce at higher prices than their new competitors.

These effects were observed following the entry into force of NAFTA in January 1994.(2) Labour productivity increased across North America.(3) In Canada, it increased by an estimated 14%, a huge leap suggesting that the least efficient companies closed down and the rest experienced growth, became more innovative, and increasingly adopted advanced technologies.(4)

Customs duties reductions led to additional increases in trade with the other two countries of 11% in Canada, 41% in the United States, and 118% in Mexico, for the period between 1993 and 2011.(5) In terms of value, American trade with Canada and Mexico increased from US$481 billion in 1993 to US$1.1 trillion in 2015.(6) While Donald Trump claims that Americans “don’t make anything anymore,” implying that NAFTA is to blame,(7) the American manufacturing sector has increased production by 58% since the deal came into effect.(8)

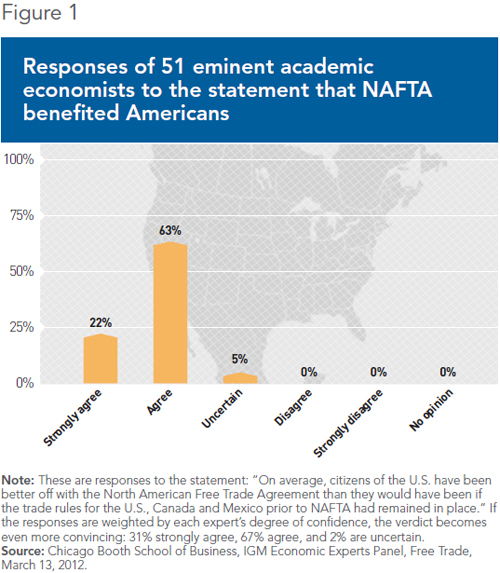

Figure 1 shows that practically every one of the 51 eminent academic economists surveyed as part of the IGM Economic Experts Panel are of the opinion that NAFTA was beneficial for Americans. Not one believes that this agreement made them worse off.

There is no question that, as Donald Trump likes to repeat, there are far fewer jobs in the manufacturing sector in the United States than there used to be—29% fewer than before NAFTA came into effect.(9) However, this change is mainly due to technical innovations that increase productivity and allow the standard of living to rise.(10)

During the ten years following the entry into force of NAFTA, the opening up of borders was by itself responsible for an increase in real wages in the companies concerned of 0.32% in Canada and of 0.11% in the United States.(11) NAFTA led to the creation of jobs in exporting industries, which pay wages that are 15% to 20% higher on average than industries that focus on domestic production.(12)

An Integrated Continental Economy

These data do not capture all of the effects of free trade, however. One of these important effects, having benefited everyone, is that production between countries is now better integrated thanks to a deeper division of labour. This phenomenon of integration is such that in many cases, imports stimulate domestic production instead of replacing it. Around 25% of American imports from Canada are products of American design, or that were assembled or processed there, and then reimported. In the case of American imports from Mexico, this figure climbs to 40%.(13)

Another positive effect of the liberalization of trade, often overlooked in these debates, is the effect on the Mexican economy. Mexico is a country whose economy struggled for a long time, for a multitude of underlying reasons. NAFTA, however, reduced the price of many consumption goods by half in just a few years, which has helped improve the still precarious living conditions of many Mexicans. The World Bank estimated in 2004 that NAFTA had lifted 3 million Mexicans above the poverty line.(14)

Yet these numerous benefits of free trade have not prevented fear-mongers from exaggerating the negative effects of NAFTA. Already in 1998, four years after the deal was signed, certain Canadian critics claimed that “Canada faces extinction as an independent nation.”(15) Clearly this threat, which brings to mind Donald Trump’s recent remarks, never materialized.

Free trade has an undeniably positive effect on the economy. If Donald Trump wants to negotiate “a better deal” for the United States, it should be an agreement that liberalizes trade even further.

This Viewpoint was prepared by Mathieu Bédard, Economist at the MEI. He holds a PhD in economics from Aix-Marseille University, and a master’s degree in economic analysis of institutions from Paul Cézanne University. The MEI’s Regulation Series seeks to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

References

1. Donald Trump, “Transcript: Donald Trump’s Foreign Policy Speech,” The New York Times, April 27, 2016.

2. NAFTA followed the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (FTA) which came into effect in January 1989.

3. Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Jeffrey J. Schott, NAFTA Revisited: Achievements and Challenges, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2005, pp. 61-62.

4. Daniel Trefler, “The Long and Short of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 94, No. 4, 2004, pp. 870-895; Alla Lileeva and Daniel Trefler, “Improved Access to Foreign Markets Raises Plant-level Productivity… for Some Plants,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 125, No. 3, 2010, pp. 1051-1099.

5. Lorenzo Caliendo and Fernando Parro, “Estimates of the Trade and Welfare Effects of NAFTA,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 82, No. 1, 2015, pp. 3 and 27.

6. United States Census Bureau, Trade in Goods with Canada, Trade in Goods with Mexico.

7. Chris Wallace, Interview with Donald J. Trump, Fox News Sunday, Fox News, November 18, 2015.

8. US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Manufacturing Sector: Real Output [OUTMS], FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, May 9, 2016.

9. US Bureau of Labor Statistics, All Employees: Manufacturing [MANEMP], FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, May 9, 2016.

10. N. Gregory Mankiw, “The Economy Is Rigged, and Other Campaign Myths,” The New York Times, May 8, 2016. The economic crises of 2001 and 2008 also considerably reduced the number of these jobs.

11. Lorenzo Caliendo and Fernando Parro, op. cit., endnote 5, p. 20.

12. Carla A. Hills, “NAFTA’s Economic Upsides,” Foreign Affairs, December 6, 2013.

13. Robert Koopman et al., “Give Credit Where Credit Is Due: Tracing Value Added in Global Production Chains,” NBER Working Paper Series, No. 16426, 2010, p. 7 (Appendix).

14. Alessandro Nicita, “Who Benefited from Trade Liberalization in Mexico? Measuring the Effects on Household Welfare,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3265, April 2004, pp. 30 and 47.

15. Maude Barlow and Bruce Campbell, Take Back the Nation 2: Meeting the Threat of NAFTA, Key Porter Books, 1993, p. vii.