Do We Need a Public Drug Insurance Monopoly in Canada?

In the last few months, the issue of drug insurance has returned to the forefront of public debate in Canada. Some of those speaking out on the topic have suggested replacing the current mixed public-private system run by the provinces with a fully public national pharmacare plan to make sure everyone is covered and to reduce costs. But this type of plan risks harming Canadians by limiting their access to drugs.

Media release: A public pharmacare monopoly would harm Canadians

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

|

The risks that come with a national pharmacare program (The Globe and Mail, July 24, 2015)

Assurance médicaments : plus qu’une question d’argent (ARGENT, August 11, 2015) National pharmacare plan not the answer (Ottawa Citizen, August 19, 2015) |

Interview (in French) with Yanick Labrie (C’est pas trop tôt!, Radio-Canada, August 11, 2015)

Interview (in French) with Yanick Labrie (Normandeau-Duhaime, FM93, August 11, 2015) Interview (in French) with Yanick Labrie (Radio-Canada International, August 12, 2015) |

Interview (in French) with Yanick Labrie (Salut bonjour!, TVA-TV, August 11, 2015) |

Do We Need a Public Drug Insurance Monopoly in Canada?

Over the past few months, the issue of prescription drug insurance has returned to the forefront of public debate in Canada. In June, eight provincial health ministers took part in a roundtable discussion with health professionals and experts in the field in order to discuss the relevance of reforming the current system, which leaves some Canadians with incomplete insurance coverage.(1) Their voices join those of activists who have for several years now been proposing the adoption of a fully public national prescription drug insurance plan, to replace Canada’s current mixed public-private system administered by the provinces.(2)

Would the adoption of a single-payer drug insurance plan be of benefit to Canadians? Is the universal plan put in place in Quebec, which relies on a range of insurers, a better model for the other provinces to emulate? This Economic Note looks into these important questions.

Incomplete Insurance Coverage

Currently, 42% of prescription drug spending in the country is paid for by public insurance plans. The remaining expenditures are funded privately, either directly by patients themselves (22.2%), or through their private insurance plans (35.8%).(3)

The provinces all offer public drug insurance coverage for various groups within their populations. Low-income seniors and children, as well as welfare recipients and people suffering from certain serious illnesses, enjoy complete or nearly complete coverage in each province.(4) In all, some 98% of the Canadian population has drug insurance coverage, either private or public, according to the most reliable estimates from the mid-2000s.(5)

Thus, even though each province currently has programs in place designed to protect certain vulnerable groups, it is true that a small fraction of the population has no insurance and may therefore find themselves in difficulty facing high prescription drug expenditures.

Researchers recently carried out an in-depth study of the financial burden that different categories of households have to take on. The results of their research demonstrate that only a very small minority of Canadian households have to deal with catastrophic expenditures for medicines over the course of a given year. Statistics Canada data show that on average, 1.1% of households have to devote more than 9% of their budgets (excluding durable goods) to the purchase of prescription drugs. The percentage ranges from 0.2% in Quebec to 2.2% in Newfoundland and Labrador.(6)

It is important, however, to put these data into perspective because the situation is not very different in other industrialized countries. According to a recent Commonwealth Fund report, Canada is even better than most of the 11 countries evaluated when it comes to prescription drug access for the less fortunate. In 2013, only 8% of Canadians with below-average incomes said they had not taken a drug because of cost. In comparison, this percentage was 11% in France, 14% in Australia, and 18% in New Zealand.(7)

What must be understood is that the public insurance plans in place in other OECD countries, even those that are universal, do not cover pharmaceutical expenses in their entirety. A non-negligible portion of costs must be paid by the insured, and this generally accounts for a larger share of total prescription drug spending in those countries than it does in Canada. For purposes of comparison, out-of-pocket expenses represent over 40% of total spending in Australia, Norway, Finland, and Sweden, all countries with public drug insurance plans covering their entire populations (see Figure 1).

The Hidden Costs of a Public Monopoly

Some analysts maintain that the adoption of a monopolistic insurance plan in Canada would be better able to contain prescription drug costs than a mixed public-private system administered by the provinces like the one currently in place in this country. Such a plan would provide the public insurer with greater negotiating power in dealing with pharmaceutical companies, which would allow it to obtain significant concessions in terms of drug prices.(8) What they fail to mention, however, is that savings would come from increased rationing rather than from greater efficiency.

Not only would putting in place a pan-Canadian public insurance scheme entail additional costs for taxpayers, but it would in no way alter governments’ current propensity to restrict access to new drugs. Foreign experience has much to teach us about the dangers of adopting a monopolistic drug insurance system here in Canada.

The United Kingdom is one of the countries that have pushed this logic the furthest.(9) Since the 1990s, there has been one policy after another aimed at controlling spending, and patients continue to suffer the consequences. For example, English patients for a number of years had to do without approved drugs that were available all across Europe. This remains the case for numerous cancer drugs that have proven their effectiveness.(10)

These restrictions probably have a role to play in the lower survival rates for various cancers in the United Kingdom compared to most industrialized countries.(11) According to a report that appeared in the medical journal The Lancet in March, the United Kingdom has among the worst results of all industrialized countries when it comes to survival rates for the ten types of cancer examined. For liver and lung cancers, the five-year survival rates are 50% lower than those observed in Canada.(12) These mediocre results are obtained despite the fact that the screening rates for many types of cancers in the United Kingdom are among the highest in the world.(13)

In New Zealand, another country frequently elevated to the status of a model to be emulated, patients’ access to innovative drugs is just as restricted as it is in the United Kingdom, if not more so.(14) Countless reports have provided accounts of the negative health outcomes entailed by the spending cap policies adopted in this country over the past two decades.(15)

For instance, of all the drugs approved in the country from January 2009 to December 2014, barely 13% were added to the formulary of products reimbursable by the public insurance plan, the worst result among the 20 countries that were evaluated.(16) According to a recent study, 75% of general practitioners reported that they had wanted to prescribe a drug in the previous six months that was not reimbursed in New Zealand.(17)

The restrictive policies of the public PHARMAC agency greatly limit the ability of doctors to prescribe what they think are the most effective drugs for meeting the needs of their patients. Because insufficient attention is paid to the fact that patients do not all react the same way when they take medications,(18) some of them are unnecessarily exposed to risks of aggravating their health conditions.

Quebec’s Mixed Universal Plan

In 1997, Quebec implemented a reform to make drug insurance coverage in the province universal. A person whose employer provides a private insurance plan must subscribe to it, as must his or her spouse and dependent children. As for others, they are covered by the Public Prescription Drug Insurance Plan. In 2012, 3.5 million Quebecers, or a little over 40% of the population, were covered by this plan. Around half of these enjoy complete coverage with no copayments or deductibles.(19)

While it is true that the costs of the system have risen since its implementation, this is in large part because Quebec has resisted, more than the other provinces have, the temptation to ration access to innovative drugs. Indeed, when comparing provincial public drug insurance plans in place today, Quebec provides the most generous coverage by far. Whereas on average 23% of all drugs approved by Health Canada between 2004 and 2012 were found on the formularies of reimbursable products of Canada’s provincial public plans in December 2013, in Quebec the proportion was 38%.(20)

The Quebec population spends more on medicines than those of the other provinces, but this is essentially due to a larger volume of prescriptions (80% of the difference) and not to higher prices for drugs.(21) It is also important to note that this greater spending on drugs coincides with lower spending in the public health care system than elsewhere in the country. As the hospitalization rate has been trending downward since the start of the 2000s, we can deduce that more accessible pharmaceutical therapies in Quebec have likely replaced other kinds of more expensive medical care, like surgeries in a hospital setting.(22)

Does this mean that the health of Quebecers is suffering? On the contrary, health results are even better than those observed in most other provinces. Of all provinces, Quebec has the highest rates of prescriptions for and spending on drugs to treat cardiovascular disease.(23) At the same time, it has the best results in Canada in terms of premature mortality and mortality related to cardiovascular disease.(24)

The Quebec system is obviously not perfect. Public coverage is not as generous as that of private plans,(25) and in all likelihood, policies designed to control spending have repercussions on those insured by private plans who must in turn pay more for their prescription drugs.

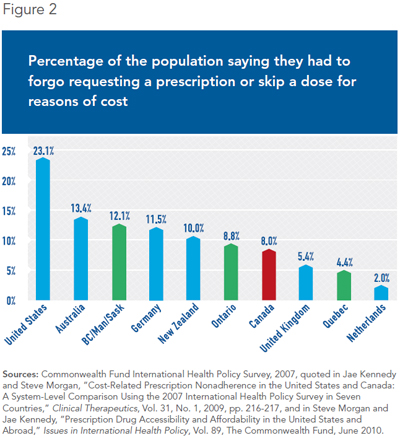

Nonetheless, the mixed universal Quebec plan manages to provide insurance coverage to all residents. Thus, Quebecers are less likely (4.4%) to say they had to forgo taking their medicines or skip a dose for financial reasons than the residents of all other Canadian provinces, and of a good number of countries including Australia (13.4%), New Zealand (10%), and the United Kingdom (5.4%) (see Figure 2).

Conclusion

Canadians should be wary of the idea of replacing our mixed system with what exists in the United Kingdom or in New Zealand. Socializing a larger portion of prescription drug spending through a monopolistic insurance scheme would end up giving more power to governments and bureaucrats to make decisions and trade-offs on behalf of the insured. Policies that restrict access to new drugs would be applied across the board and would penalize all Canadians in the same way.

Most Canadians already understand this dynamic. Indeed, according to a poll published last month, only 31% of respondents said they favoured replacing our current mixed public-private plans administered by the provinces with a national drug insurance monopoly.(26) While Canadians realize that wanting to improve access to drugs for all is a worthwhile goal, they are not ready to settle for lower-quality drug insurance coverage than what they currently enjoy.

This Economic Note was prepared by Yanick Labrie, Economist at the Montreal Economic Institute and holder of a master’s degree in economics (Université de Montréal). The MEI’s Health Care Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and private initiative lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

References

1. Keith Leslie, “Provincial health ministers call for national pharmacare program,” The Globe and Mail, June 8, 2015.

2. See among others Steve Morgan and Jamie Daw, “National pharmacare plan overdue,” Toronto Star, August 21, 2012; Eric Hoskins, “Why Canada needs a national pharmacare program,” The Globe and Mail, October 14, 2014; “Editorial: Canada needs a national pharmacare plan,” Toronto Star, July 19, 2015.

3. Canadian Institute for Health Information, Prescribed Drug Spending in Canada, 2013: A Focus on Public Drug Programs, Spending and Health Workforce, May 2015, p. 11.

4. See Nadeem Esmail and Bacchus Barua, Drug Coverage for Low-Income Families, Fraser Institute, April 2015.

5. Ken Fraser, The Challenge of Catastrophic Drug Coverage, Fraser Group, May 2006, p. 10.

6. Sam Caldbick et al., “The financial burden of out of pocket prescription drug expenses in Canada,” International Journal of Health Economics and Management (forthcoming).

7. Karen Davis et al., Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: How the Performance of the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally, The Commonwealth Fund, June 2014, p. 24.

8. Steve Morgan, “Single-payer pharmacare would save billions,” Healthy Debate, February 13, 2013.

9. We should add that the United Kingdom, like other countries having adopted a universal public drug insurance plan, does not prohibit the purchase of private drug insurance policies covering a wider range of innovative drugs. See A. B. Metha and E. Low, “Access to Expensive Drugs in the NHS: Myths and Realities for Cancer Patients,” International Journal of Clinical Practice, Vol. 61, No. 12, December 2007, pp. 2126-2129.

10. See among others Rosa Prince, “Life-saving cancer drugs still not available on NHS,” The Telegraph, April 3, 2010; Laura Donnelly and Gregory Walton, “25 cancer drugs to be denied on NHS,” The Telegraph, January 12, 2015; Mike Richards, Extent and Causes of International Variations in Drug Usage, Report for the Secretary of State, Department of Health, Government of England, July 2010.

11. M. Abdel-Rahman et al., “What If Cancer Survival in Britain Were the Same as in Europe: How Many Deaths Are Avoidable?” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 101, December 2009, pp. 115-124.

12. Claudia Allemani et al., “Global Surveillance of Cancer Survival 1995-2009: Analysis of Individual Data for 25 676 887 Patients from 279 Population-Based Registries in 67 Countries (CONCORD-2),” The Lancet, Vol. 385, No. 9972, March 2015, pp. 977-1010.

13. Lucia Kossarova, Ian Blunt and Martin Bardsley, Focus On: International Comparisons of Healthcare Quality: What Can the UK Learn? The Health Foundation and The Nuffield Trust, July 2015, pp. 27-32.

14. Rajan Ragupathy et al., “A 3-Dimensional View of Access to Licensed and Subsidized Medicines under Single-Payer Systems in the US, the UK, Australia and New Zealand,” Pharmacoeconomics, Vol. 30, No. 11, 2012, pp. 1051-1065; Michael Wonder and Richard Milne, “Access to New Medicines in New Zealand Compared to Australia,” The New Zealand Medical Journal, Vol. 124, No. 1346, 2011, pp. 12-28.

15. See among others Chris Ellis and Harvey White, “PHARMAC and the Statin Debacle,” The New Zealand Medical Journal, Vol. 119, No. 1236, June 2006, pp. 84-94; Jacques LeLorier and NSB Rawson, “Lessons for a National Pharmaceuticals Strategy in Canada from Australia and New Zealand,” Canadian Journal of Cardiology, Vol. 23, No. 9, July 2007, pp. 711-718.

16. Danielle Nicholson, “New Zealand access to medicine worst in OECD,” New Zealand Herald, March 20, 2015.

17. Zaheer-Ud-Din Babar et al., “Evaluating General Practitioners’ Opinions on Issues Concerning Access to Medicines in New Zealand,” Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research (forthcoming, 2015).

18. William E. Evans and Howard L. McLoad, “Pharmacogenomics – Drug Disposition, Drug Targets and Side Effects,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 348, No. 6, 2003, pp. 538-549.

19. Claude Montmarquette, Stéphanie Boulenger and Joanne Castonguay, “Les risques liés à la création de PHARMA-QUÉBEC,” Project Report 2014-RP-05, CIRANO, April 2014, p. 15.

20. Canadian Health Policy Institute, “Comparing Access to New Drugs in Canada’s Federal and Provincial Public Drug Plans,” Canadian Health Policy, June 2014, p. 9.

21. Kate Smolina and Steve Morgan, “The Drivers of Overspending on Prescription Drugs in Quebec,” Healthcare Policy, Vol. 10, No. 2, November 2014, pp. 22-23.

22. Claude Montmarquette, Stéphanie Boulenger and Joanne Castonguay, op.cit., footnote 19, pp. 13-15.

23. Kate Smolina and Steve Morgan, op. cit., footnote 21.

24. Conference Board of Canada, Provincial and Territorial Ranking for Health, What does the provincial health report card look like?; Conference Board of Canada, Provincial and Territorial Ranking for Health, Premature Mortality.

25. Canadian Health Policy Institute, “Private versus Public Drug Coverage in Canada: Experience Shows Competition and Choice Are Better than Government-Run Pharmacare,” Canadian Health Policy, February 2014.

26. Abacus Data, “National Pharmacare in Canada,” A survey of Canadian attitudes towards developing a national pharmacare program commissioned by the Canadian Pharmacists Association, July 16, 2015, p. 7.