Viewpoint – The Chaoulli Decision and Health Care Reform: A Missed Opportunity?

Ten years have passed since the Chaoulli decision, handed down by the Supreme Court of Canada in June 2005. The highest court in the land ruled then that when the government is unable to offer access to needed care within a reasonable time frame, the prohibition against purchasing private health insurance is a violation of the right to life and security of patients and runs counter to the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms. How have waiting times in Quebec’s public health care system evolved since the Chaoulli decision? Have the reforms adopted on the heels of the ruling improved patients’ access to health care?

Media release: Ten years after the Chaoulli decision, Quebec patients are still waiting as long as ever

Technical Annex (in French only)

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Dix ans de l’arrêt Chaoulli : «Statu quo» dans le réseau de la Santé, selon l’Institut économique de Montréal (Le Journal de Montréal, June 4, 2015)

Le jugement Chaoulli: un rendez-vous manqué (Le Devoir, June 5, 2015) Still waiting – the Chaoulli decision, 10 years later (Montreal Gazette, June 8, 2015) |

Comment (in French) by Éric Duhaime and Nathalie Normandeau, radio hosts (Normandeau-Duhaime, FM93, June 4, 2015) | Comment (in French) by TV host Mario Dumont (Le Québec matin, LCN, June 4, 2015)

Interview (in French) with Yanick Labrie (Mario Dumont, LCN, June 4, 2015) |

The Chaoulli Decision and Health Care Reform: A Missed Opportunity?

Ten years have passed since the Chaoulli decision, handed down by the Supreme Court of Canada in June 2005. The highest court in the land ruled then that when the government is unable to offer access to needed care within a reasonable time frame, the prohibition against purchasing private health insurance is a violation of the right to life and security of patients and runs counter to the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms.

The decision rested on the premise that long wait times in the public health care system entail irreversible harm and suffering for patients, and even premature death in certain cases. “Access to a waiting list is not access to health care,” declared Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin in her verdict.(1)

How have waiting times in Quebec’s public health care system evolved since the Chaoulli decision? Have the reforms adopted on the heels of the ruling improved patients’ access to health care?

Still Waiting

The Court’s decision hinted at several major changes in public policies regarding health care services in Quebec. The government’s response, however, was very timid. After a reprieve granted by the Court, the government finally adopted a bill in December 2006 in order to comply with the ruling.(2) Three reforms followed from this.

1) Duplicate private insurance

In principle, the legislative change authorized Quebecers to purchase duplicate private insurance for a limited number of medical and surgical treatments, such as hip and knee replacements and cataract removals.

In practice, however, no actual market for this kind of insurance developed, the number of admissible surgeries being too low for new and interesting insurance products for individuals and employers to appear. The maintenance of the prohibition on mixed medical practice also hampered the emergence of such an insurance market.

2) Specialized medical centres

The new legal provisions aimed to provide a tighter regulatory framework for private surgery clinics—newly referred to as specialized medical centres. The law also authorized public hospitals to sign partnership agreements with clinics for the transfer of a certain volume of surgeries and treatments (which remained covered by the public system).

While the number of centres has grown since 2006, these remain marginal in Quebec’s hospital landscape. In May 2014, there were 43 specialized medical centres in Quebec, basically small in size, most of which specialize in plastic and cosmetic surgery.(3) Only a minority of them provide medically required health care services, and they do so almost exclusively in the context of partnership agreements signed with public hospitals. Three agreements of this type signed in recent years led to significantly improved access in the public hospitals concerned.(4)

3) A mechanism for managing wait times

A new information system to track the evolution of wait times for elective surgery was created and came into effect in June 2007. The government set the maximum wait time for treatment at six months for hip, knee, and cataract surgery.(5)

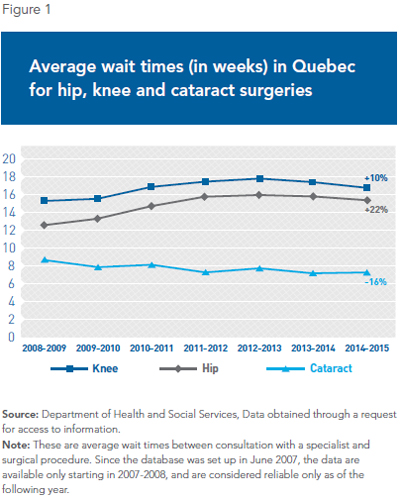

This database allows us to observe that wait times for elective surgeries have remained relatively constant in Quebec since 2008, on average.(6) In the case of hip and knee surgery, wait times between consultation with a specialist and medical procedure have gone up, increasing to over 15 weeks in recent years(7) (see Figure 1).

It is true, as certain experts have pointed out,(8) that the number of elective surgeries performed has increased since the early 2000s, in conjunction with the aging of the population. However, this trend did not accelerate starting in 2007.(9) Moreover, of all the Canadian provinces, it is in Quebec that we find the lowest numbers of hip and knee replacements as a proportion of the adult population.(10)

As for the maximum wait time targets set at six months by the government, they have generally not been met for many patients. Nearly one patient in five must still wait over six months for a hip or knee operation.

Conclusion

In the end, we can see that waiting times have changed very little in Quebec since the Chaoulli decision. The government chose to interpret the Supreme Court’s ruling narrowly, and the timid reforms adopted have not led to improved access for hip, knee, and cataract surgeries. Patients waiting for treatment have very few options outside the public system.

Ten years later, Judge McLachlin’s statement is as relevant as ever. As of March 31, 2015, nearly 20,000 Quebecers had been waiting for surgery for more than six months in the public health care system.(11) When the government is unable to offer access to care in a timely manner, there is no justification for maintaining a strict monopoly on the delivery of required medical care. It is time to adopt the reforms we need by taking inspiration from Europe’s mixed universal systems, which are far more accessible to patients.(12)

This Viewpoint was prepared by Yanick Labrie, Economist at the Montreal Economic Institute and holder of a master’s degree in economics (Université de Montréal). The MEI’s Health Care Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and private initiative lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

References

1. Supreme Court of Canada, Chaoulli v. Quebec (Attorney General), 2005.

2. Government of Quebec, An Act to amend the Act respecting health services and social services and other legislative provisions, 2006.

3. Department of Health and Social Services, Liste des centres médicaux spécialisés ayant reçu un permis en date du 6 mai 2014, 2014.

4. See among others Ronald Denis, “Moins d’attente, plus d’opérations,” La Presse, June 6, 2011; Mathieu Courchesne, “Cité-de-la-santé : six mois d’attente pour être opéré,” Le Journal de Montréal, February 16, 2013; Françoise Le Guen, “L’Institut de l’œil des Laurentides est là pour rester,” Le Courrier, June 11, 2014.

5. Although many commentators regularly refer to a “wait-time guarantee” as if it were a legal right of patients, these are instead administrative targets for hospitals to reach. For hip and knee replacements, and for cataract removals, the target to be reached is for 90% of patients to be operated on within a maximum wait of six months.

6. According to the Expert Panel for Patient-Based Funding, average wait times for several surgical specialties decreased from 2008-2009 to 2011-2012. The data obtained from the Department of Health and Social Services did not allow us to confirm these results. See Government of Quebec, Better Access to Surgery – An Expanded Activity-Based Funding Program, Technical Paper 1, Expert Panel for Patient-Based Funding, February 2014, p. 13.

7. Department of Health and Social Services, Accès aux chirurgies par agence et pour l’ensemble du Québec – Réalisées, 2015.

8. Op. cit., footnote 6, p. 11.

9. See Technical Annex on the MEI’s website.

10. Health and Welfare Commissioner, La performance du système de santé et de services sociaux québécois, 2014, p. 36.

11. Department of Health and Social Services, Accès aux chirurgies par agence et pour l’ensemble du Québec – En attente, 2015.

12. Yanick Labrie, For a Universal and Efficient Health Care System: Six Reform Proposals, Research Paper, Montreal Economic Institute, March 2014.